Three neon signs punctuate Theaster Gates’s powerful installation of new paintings and sculptures. Progress Mill, 2018, the only work occupying the spacious entrance gallery, takes the form of a single generic infographic. White and red neon tubes delineate the circular symmetry of a reductive pie chart outlined in black, seemingly bereft of any textual information but in fact adapted from W. E. B. Du Bois’s visualizations of Black demographics in the United States in 1900—specifically Du Bois’s black-and-red line drawing titled “Proportions of Whites and Negroes in the different classes of occupations in the United States.” (Such statistical diagrams were also a source for a series of paintings and drawings that Gates began in 2014.) The title and graphic language of Progress Mill, divorced from its specific conclusions, point toward the clichés of social and technological advancement, such as the “wheel of progress” and the millstone, with its evocation of physical labor. The same social and formal interpretations can also be applied to Gates’s blue-neon composition Slaves, Ex Slaves, 2018. Hanging in the voluminous main gallery, the nearly square, black geometric form hosts a series of glowing indigo lines that run down from its upper edge, leaving a void of black space in the center of the form, a mass of data that cannot be read. This codification of data may seem to undermine the work’s potential to persuade viewers of particular inequities, but it also invites a potent response: the viewer’s own projections. What imbalance might be represented here? What disparate conclusions might viewers reach from the same data? Another historic set of statistics, the infamous Moynihan Report of 1965, comes to mind as an example of the harmful effects of data analysis performed by prejudiced observers.

At the heart of Gates’s exhibition is a very different kind of logo that similarly unfolds into social critique. Suspended from the ceiling, a formidable vintage Rothschild Liquors sign—obtained from one of the Chicago chain’s many recently closed marts—commands attention. The family-owned store’s iconic two-sided neon advertisement (featured in Kerry James Marshall’s painting 7am Sunday Morning, 2003) now floats in the gallery at eye level. Between the two radiant red words spelling out the establishment’s name, Gates inserted his own white-neon glass tubing that reads MAMA’S MILK in cursive. The juxtaposition, equating alcohol and breast milk, highlights the mutual dependency of the once-widespread chain and economically depressed communities, where alcoholism can have the most damaging effects. At the same time, the work’s dazzling luminescence, electrical hum, and hulking form offer affecting pleasures that temper Gates’s social critique.

The other massive piece in the show, Every Square, 2019, recalls another Chicago landmark associated with societal ills, albeit in a different sense: Mies van der Rohe’s Federal Center, which houses the courthouse, Drug Enforcement Administration, Department of Labor, and other entities. The complex was designed so that all elements would align with a grid, centered on a common courtyard; the buildings themselves feature double-height ground floors with supporting I beams. Gates’s installation mirrors this effect with scaffolding perched above a large metal stage with a central gridded floor. Two sets of flanking stairs invite viewers to walk around the perimeter of the elevated platform. On top of the grated deck rest a large, hand-built ceramic vessel and two roughhewn wooden bases. The smaller base supports a large angular rock, while the other hosts a mask with long horns.

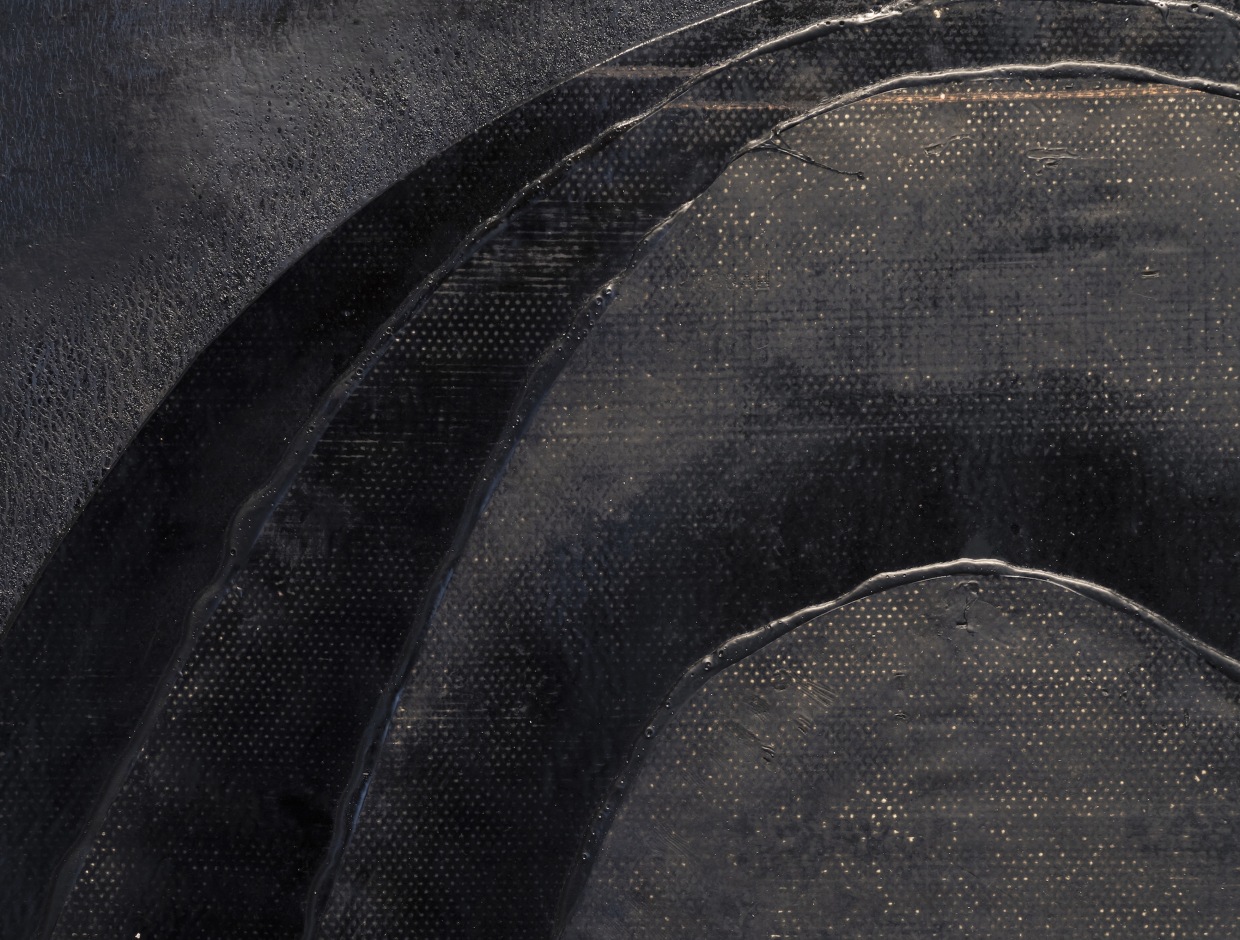

Gates’s emphasis on the city as organizing device ties in effectively to his conceptual work with American society at large. Yet this systematic approach is couched within the elements of the exhibition that are not manufactured but are imprinted with traces of vulnerable, human labor. For instance, three paintings in the show—Highway with Mountain, Black Rainbow, and Arc, all 2019—are composed from pieces of cut waterproof roofing membrane patched together with tar. Apart from the slight tonal shifts between the black materials, the only hints of color are the narrow orange register lines printed on the roofing material. Collaging abstract motifs with materials associated with manual labor, Gates extends his engagement with work done by hand as a rich marker of race and class.

— Michelle Grabner